As the TUNESS fundraising team continues its campaign to collect funds to finance the school supplies for all pupils (from 1st to 6th grades) attending an elementary school located in a disadvantaged region of the northern part of Tunisia, this weekly note focuses on the serious problem of school dropouts. Research have shown school dropouts are very often among the most vulnerable population in terms of regular income and/or chances to access decent jobs. Moreover, a high percentage of prison population is frequently found to have records of unstable school attendance or misbehavior at early years of education. While an accurate estimate of the scope of this problem remains difficult to elaborate, some encouraging initiatives at both national and international levels have made to shed some light on this issue.

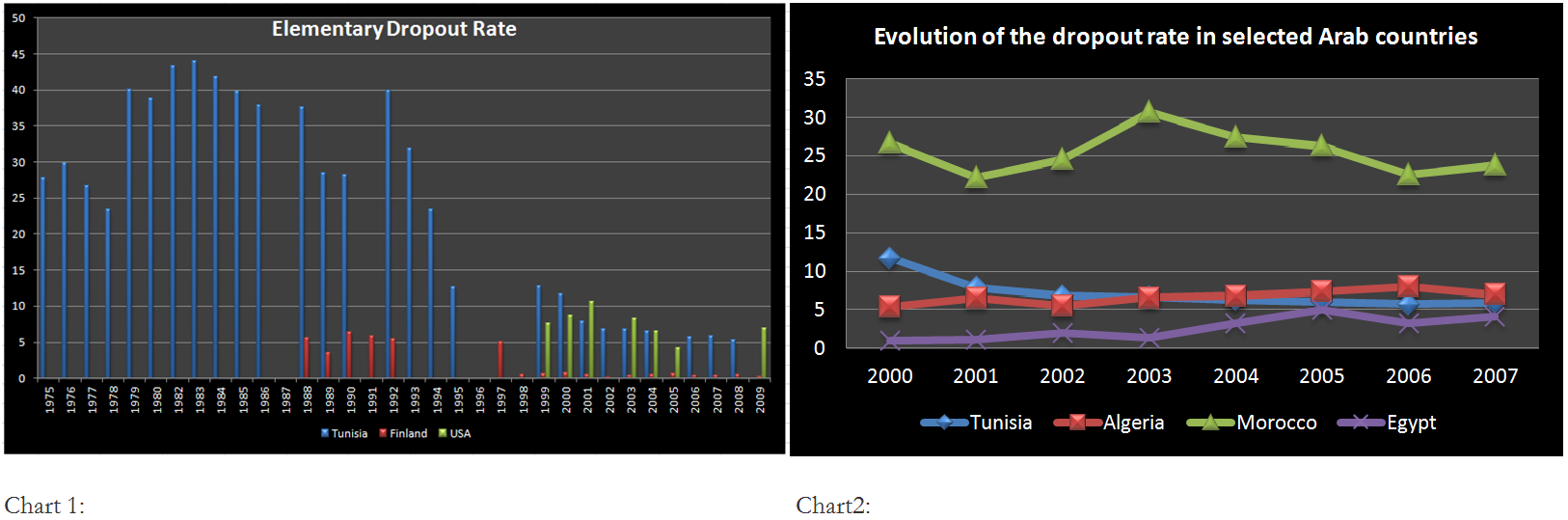

Chart1 presents the dropout rate for Tunisia, USA, and Finland. In Tunisia, the dropout rate displays 2 distinct phases namely, pre and post 1991. There is clear dropout rate decay in the post 1991 period which is mainly due to the ratification of article 2, initially enacted in 1958, that made education compulsory for kids between the age of 6 to 16 years old. It took 4 years to bring the levels down to 12% from 35% and approximately 10 years to start hovering at around 5%. Ideally, one should expect the dropout rate to be lowered further to a level similar to certain developed countries such as Finland with dropout rate approaching zero.

Not surprising to find that most countries, in the recent period, have given a particular attention to tackle this school dropout problem. Drastic measures were designed at all levels within specialized international organizations and government agencies to first identify students at risk of dropping out.Family conditions, socioeconomic constraints, lack of security and infrastructure are among the key factors that are often flagged as the most frequent reasons for deserting schools. Generally speaking, it has been found that the disengagement of students from formal education is primarily due to factors that are unrelated to the student’s own behavior and/or his perception of the importance of education.

According to recent studies: “the dropping out is more likely to occur among students from single-parent families and students with an older sibiling who has already dropped out than among counterparts without those characteristics. Other aspect of the student’s home life such as the level of parental involvement and support , parent’s educational expectations , parent’s attitude about school, and stability of the family environment can also influence a youth’s decision to stay or not in a school”.

Chart 2 above shows that across selected Arab countries, the dropout rate does not seem to change substantially throughout the period under investigation. While, as we pointed out above, we suspect that aggregate national figures may hide further discrepancies when either minority groups, (i.e. in the USA the dropout rate amongst Hispanics and Black have been documented to be higher than average while Asian-American are significantly lower than average), or geographic regions are considered, unfortunately we are unable to search that more comprehensively due to the absence of reliable statistics.

Multiple approaches have been elaborated, with mixed results, to prevent this problem and improve the effectiveness of local efforts to reduce the disengagements of students at early age. We identify below some of the recommendations that are often advanced by national practitioners and childhood education experts to reduce the dropout rate. Those recommendations can be broken down into two main groups based on their respective underlying factors;

1. Dropout resulting from the quality of education

The world economic forum list many Scandinavian and European countries with high quality education index, as such it is not surprise that they have the low dropout rate. Finland started implementing an aggressive educational reform campaign since the 1980s. As could be observed from chart 1 during the 1990, Finland dropout rate was hovering around 5% and went down further to decimal levels after the year 2000. The greater performance of Finland was thoroughly studies by Shalbert (2009) among many others.

Students who have frequently repeated several grades have high odds to give up their education at early stage. Providing an adequate academic support to those identified with high risk of dropout and closely monitor their academic progress is undoubtedly the most effective way to tackle this problem at its roots. It is important to note that several dropout prevention programs in the world were able to limit the problem simply by ensuring supplemental services (e.g., tutoring, social support) during and after school time. The investment in supplemental education services should be made as soon as the high risk population is identified. Recent studies have in fact pointed out that: “when students enter school without the required knowledge and skills to succeed, they start the race one lap behind and never catch up”.

Next, we highlight the main reasons for the success of those dropout prevention programs;

- Better qualified teachers (for instance in Finland, teachers are required to take 3,4, and in some cases 5 more years of graduate studies after college – a master's degree is required - with only 15% admittance rate for the program);

- Intensive early intervention when pupils have problems. More resources should be allocated to those that need it the most. The Finish model, for instance, is based on training teachers to carry out research and find solutions. This constitutes a paradigm shift from the outdated model that follows the syllabi technique;

- A teacher with a master's degree must be paid better than college graduate. This approach provides a significant financial incentive for teachers. Many have however questioned the budgetary burden associated with this incremental financial incentive for teachers. But wouldn’t that be more effective approach than paying for police and prison cells?

2. Dropout resulting from family characteristics

As stated above, family background factors remain the major causes of dropout. In order to ensure a high level of effectiveness in addressing this problem, a large variety of initiatives were carried out in several countries. Those initiatives can be clustered around different features of the student’s environment. We highlight below few of those widely implemented measures;

- Identify children whose parents are in very difficult economic conditions. Several government entities are expected to coordinate their efforts to provide those families with decent conditions of life. This should encourage at risk student to focus on his education and not worry about leaving school prematurely to help parents in their daily struggle for a decent household income;

- Encourage parents to be more involved in the education process of their children. Requesting teachers to reach out to parents to invite them on a regular basis to be aware of their children’s school performance at school is critical to achieve this goal. Not surprising to find that the emotional and cognitive development of students can only be achieved when the latter feel surrounded by family members who care and value such a development;

- Improve school and classroom conditions in order to reduce any hazard or negative experience that could be associated with school attendance for those students;

- Encourage various components of the civil society to take up certain tasks in terms of providing logistic supports and/or social counseling particularly when central government is unable to carry out its role.

In the present note we attempted to briefly describe certain causes of the school dropout problem. Some concrete recommendations were also made to help prevent the proliferation of this problem. While the financial implications associated with those actions might be important and thus could constitute a major obstacle for the implementation in poor countries, past results have unequivocally shown their effectiveness in reducing the scope of the problem.

This note is prepared by Bechir Bouzid and Zied Driss TUNESS Research Team.

References:

P. Sahlberg, 2009, Educational Change in Finland, in A. Hargreaves, M. Fullan, A. Lieberman, and D. Hopkins (Eds.), International Handbook of Educational Change

National Report on Millennium Development Goal UN 2004

Alliance for Excellent Education, High School Dropout in Americal, Fact Sheet September 2010

http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=UNESCO&f=series%3ADR_1

http://www.nationsencyclopedia.com/WorldStats/Edu-primary-drop-out-rate.html

Whitehurst G JR, Whitfield S, COMPULSORY SCHOOL ATTENDANCE What Research Says and What It Means for State Policy, Brown Center at Brookings

Roekel DV Raising compulsory school age requirements: A Dropout Fix?

The first Phase of education quality improvement program EQIP, World Report No 392304, March 2007

School Characteristics Related to High School Dropout Rates, Remedial and Special education, Novemeber/ Descember 2007